Tuesday, August 26, 2008

ELDRIDGE CLEAVER SOUL STILL ON ICE

ELDRIDGE CLEAVER:

Black Man, White Woman

The Sexual Revolution in America

A Black Man Examines Sex Mores 1969

What a time it was! America was experiencing a period of incredible, noisy upheaval. The background noise was pumped over the airwaves. A vital form of new music registered its arrival in the very physical way, limbs swayed, feet thumped and singing reached a new decibel level, and the lyrics seemed to be written in a new code. Rock an' Roll was here to stay. No more than one generation back the culture proclaimed "I Remember Mama!" I remember arriving in New York Harbor, after completing a year and one-half graduate study in West Germany, and on the deck of the ship hearing the Rolling Stones on the New York radio station. Passions were being ignited from Great Britain to the New World, via music that had originally come to Chicago from the Mississippi Delta. The year was 1964. The season was Spring, April, when I first walked across Washington Square, and matriculated at NYU. The steady rhythm of guitars and drums in the Park signaled the eclipse, the virtual ending end of the Jazz form championed by the Beats. Yes indeed! The times, they were changing! Turned-up electronic amplification ran the acoustic folk music scene off Greenwich Village Streets.

WAR

There was another noise traveling the airwaves at this time during the 1960’s. It was the noise of war. Gunshots, aircraft on bombing runs, the cacophony of fire fights, the endless war with correspondence reporting right from the bush, capturing all the sounds of every kind of weaponry: flame throwers, helicopters, and armored speedboats powering jungle delta waters. Those sounds were apart of American living rooms, kitchens and bedrooms.

Today, it might be hard to believe, but children went to school with those sounds hammered into their heads as parents watched or listened to the morning news. Those sounds of war were the leitmotif to life. Explosive death unhinged us and led us with its constant clanging and hammering to sex, nihilistic all consuming sex, Hippie sex, drugs of every hew and kind, and protest. Injustice was now in plain view. The ultimate dichotomies of weak and strong, small and large were all over the airwaves.

THE NOISE OF PROTEST AND DISSENT

Tuesday, August 19, 2008

JULIUS CAESAR: Sex & Politics

http://abigbookofmyown.blogspot.com/

http://sites.google.com/site/stanleypacion/homepage

http://www.youtube.com/StanleyPacion

http://www.stanleypacion.com/home.html/

http://www.indiaeveryday.in/video/u/StanleyPacion.htm?ss=true

As of this date my YOUTUBE Channel has received 210,000 + Single Page Visits, Video Views! A Google Search of the terms Stanley Pacion YouTube Channel yields a result count of 400,000.

Please SUBSCRIBE BUTTON

JULIUS CAESAR: The Political Uses of Sex

A pagan man to the core, Caesar appears to have been an unscrupulous libertine who used and abused wives and mistresses to suit his sexual or political urges.

Stanley J. Pacion

Julius Gaius Caesar was the product of what some scholars have termed the Roman Renaissance, a period which roughly spans the century and a half before Christ’s birth. It was an era rooted in the learning and culture of classical Greece, but plagued by civil wars. It was a time of truly awesome upheaval which made way for the relative stability of Caesarism, a word which has come into English meaning, military or imperial dictatorship; political authoritarianism, and the imperium, a concept fully discussed in the online, Wikipedia. The Roman Renaissance witnessed the collapse of the old moral order – and abandonment of the traditional Roman ideals of chastity and sexual moderation.

I was fortunate to have had a great Caesar scholar and a scholar of ancient Roman history as my teacher and mentor for two years at Northern Illinois University. His name was John H. Collins. Dr. Collins was a man of extraordinary talent, and a great teacher. His ability to influence and fire up students to learning lives on to this day. A hall at the University commemorates his name. His fluency in languages has been noted in the above article, but his feats of memory were nothing short of awesome, mind bending. I remember one Spring day when in the middle of a class on the the Roman Republic Dr. Collins launched into a full recitation of Sallust's account of Julius Caesar's oration to the Roman Senate during the period of the so-called Catilinian Conspiracy. Sallust was a literary giant and one of ancient Rome's greatest historians, and Dr. Collins quoted from him the whole length of Chapter 51 of Sallust's history on the Conspiracy of Catiline. Collins did so in Latin, repeating the entire chapter in the sonorous, the marching tones and cadences of the Latin script. In was a truly breath taking performance, and one got the feeling of what it was to be an ancient Roman, and how fraught with danger and awful consequence life in the first century Before the Common Era truly had been. One received a real, first hand glimpse into top-notch Roman oratory. It was history, wie es eigentlich gewesen war.

In English Sallust account reads, remember it is the first time the historical figure Caesar appears in recorded history, “It becomes all men, Conscript Fathers [Oh, Fathers of the Senate!], who deliberate on dubious matters, to be influenced neither by hatred, affection, anger, nor pity. The mind, when such feelings obstruct its view, cannot easily see what is right; nor has any human being consulted, at the same moment, his passions and his interest. When the mind is freely exerted, its reasoning is sound; but passion, if it gain possession of it, becomes its tyrant, and reason is powerless."

In ancient Rome citizens could not be executed for their crimes, but were banished instead. When the Senate, led by Cicero, moved to have Catiline and his fellow conspirators executed for treason, Caesar stepped to the fore and reminded his fellow Senators that there was such a thing as the law, and to abrogate it bore dire consequence.

Born of noble stock about 100 BCE, Caesar expressed the values of this new age, much to the horror of the conservative aristocracy. He lived by what the Romans called virtu – not what we might mean by moral goodness, but vigor, ability, and success. He was an apostle of power, amoral, calculating, unscrupulous and ruthless. Remember we are dealing here in pagan times, about a century before the birth of the historical Jesus, and long before the introduction of Judaeo-Christian value system into Western civilization. Nevertheless, as many of his contemporaries have attested, he was also capable of great devotion, of fairness, and of abandoning all political or career considerations before the demands of love. Actually, Caesar’s duality – the struggle between the consummate politician and the impetuous, sometimes reckless pagan lover – had a great influence on his political life.

While I continue this account of sex and politics during Caesar's time allow me to continue the story of my education in ancient Roman history. Dr John H. Collins memory was simply, but totally photographic. Although it would take hours just to mention his feats of memory, I knew him personally able to recite most of Shakespeare from recall. I would read a verse or two, commit it to memory and challenge him on the bard's plays, and I candidly must attest he unfailingly responded with exact quotations. He told me that he knew all of Ivanhoe by rotestory, "A Stopping by a Railroad Station" by the nineteenth century, English essayist, moralist and historian James Anthony Froude.

Please allow me to continue with all these reminiscences for they do have a point, and it, if patience allows, become apparent in the next paragraph.

A bloody struggle between two major political parties dominated Roman political life at the time Caesar reached manhood. These two parties were the populares, which appealed to the less privileged classes mainly through liberal welfare measures, and the optimates, which espoused the interests of the conservative politicians and insisted on strict constitutionalism and old-time morality. Despite his aristocratic lineage, which could be traced back to the son of the legendary Aeneas, Caesar aligned himself with the populares. His patrimony also included Venus, goddess of love, a point which Caesar’s enemies never tired of repeating, especially as his amatory talents became known. At 18 he cemented his alliance with the populares by marrying the 16-year-old Cornelia, daughter of the great popular leader Cinna, who ruled Italy for three consecutive consulships from 86 to 83 B.C. In spite of the considerable political implications of the union, it appears to have been a genuine love match. The often-broke young Caesar chose Cornelia over a rich heiress, Consutia.

The ascendancy of the populares ended in November of 82 B.C. when the armies of the Dictator Sulla, a reactionary optimate, entered Rome and butchered the leaders of the opposing party. In the slaughter 90 senators were murdered, and some 350 million sesterces (roughly $35 million) of property were confiscated. The dictator soon commanded the young Caesar to divorce his wife. Caesar refused, preferring to see the confiscation of his own property and his wife’s dowry. Fearing that he would be placed on proscription, a listing which offered rewards for the dead-or-alive capture of important political enemies, Caesar fled Rome, though soon afterward, through the intervention of Caesar’s relatives, Sulla pardoned him.

Caesar returned to Rome only after Sulla’s death in 78 B.C. The intervening four years, particularly his stay at the palace of Nicomedes IV of Bithynia, far from Rome and family, afterward provided material for gossip by his enemies who were fond of relating how the young Caesar actively pursued the vices of Nicomedes’s Oriental court. Whether these accusations were true or no were simply slander has never been determined, but two things are certain: Nicomedes’s court was well known throughout the ancient word for its licentiousness, especially pederasty, and Caesar frequented it repeatedly during his self-imposed exile.

Suetonius’s The Twelve Caesars, a book noted for its gossipy revelations about the intimate lives of the early Roman Caesars or emperors, and whose portrait of the Emperor Nero I have already discussed, has kept alive some of these accusations. Among them is the charge that Nicomedes kept Caesar for pederastic purposes: “The only specific charge of unnatural practices even brought against him was that he had been King Nicomedes’s catamite – always a dark stain on his reputation and frequently quoted by his enemies. Licinius Calvus published the notorious verses:

The riches of Bithyania’s King

Who Caesar on his couch abused.

Dolabella called him ‘the Queen’s rival and inner partner of the royal bed,’ and Curio the Elder: ‘Nicomedes’s Bithynian brothel.’

Bibulus, Caesar’s colleague in the consulship, described him in an edict as ‘the Queen of Bithynia… who once wanted to sleep with a monarch, but now wants to be one.’ And Marcus Brutus recorded that about the same time, one Octavius, a scatterbrained creature who would say the first thing that came into his head, walked into a packed assembly where he saluted Pompey as ‘King’ and Caesar as ‘Queen.’ These can be discounted as mere insults, but Gaius Memmius directly charges Caesar wit having joined a group of Nicomedes’s debauched young friends at a banquet, where he acted as the royal cup-bearer; and adds that certain Roman merchants, whose names he supplies, were present as guests. Cicero, too, not only wrote in several letters: ‘Caesar was led by Nicomedes’s attendants to the royal bedchamber, where he lay on a golden couch, dressed in a purple shift… So this descendant of Venus lost his virginity in Bithyania,’ but also once interrupted Caesar while he was addressing the House in defense of Nicomedes’s daughter Nysa and listing his obligations to Nicomedes himself. ‘Enough of that,’ Cicero shouted, ‘if you please! We all know what he gave you, and what you gave him in return.’

These accusations, whether true or not, were quite persistent. Caesar’s alleged vices at Nicomedes’s court followed him even at the time of his greatest triumphs. Suetonius reported that during the Gallic triumphal procession in Rome Caesar’s own soldiers, chanting ribald songs as was the custom and privilege, intoned the following refrain: Gaul was brought to shame by Caesar; By King Nicomedes, he. Here comes Caesar, wreathed in triumph. For his Gallic victory! Nicomedes wears no laurels, Though the greatest of the three.

Cornelia died in 68 B.C., after she had borne Caesar one child, a daughter, who later married his chief political rival, Gnaeus Pompey. In a touching act of martial homage to his Cornelia, Caesar is said to have made a funeral speech in her honor from the Rostra to the people. Whenever one examines the life of this first Caesar one is always struck by his ability to be both loyal to the core, and yet a leader of incredible resolve and ruthlessness.

The period following Cornelia’s death saw the making of the legend of Caesar’s alleged sexual prowess with married women. Caesar realized that the women of his day exercised enormous power in the family circle, and he made every effort to befriend the wives of his prominent contemporaries. Among them was Tertulla, the wife of Marcus Crassus, the richest man in Rome, who loaned heavily to Caesar to finance his first campaigns. Another was Mucia, Pompey’s wife. It was whispered that Caesar supported the Gabbinian law which empowered Pompey to suppress piracy in the Mediterranean so that he would be rid of the troublesome husband. Suetonius related the scandal that followed Pompey’s divorce of Murcia and marriage to Caesar’s daughter Julia. The union cemented a political alliance between the two men which lasted until Julia’s death in childbirth. “Be this how it may, both Curio the Elder and Curio the Younger approached Pompey for having married Caesar’s daughter Julia, when it was because of Caesar, whom he had often despairingly called ‘Aegisthus,’ that he divorced Mucia, mother of his three children. This Aegisthus had been the lover of Agamemnon’s wife Clytemnestra.”

It is no exaggeration to claim that at one time Caesar was accused of having seduced the wives of all the leaders of the populares and the wives of many a notable optimate. One of the latter was Servilia, wife of the late Marcus Janius Brutus, a close ally of the reactionary Sulla, daughter of the great conservative leader Cato the Younger, and then wife of one Decimas Julius Silanus. “Servilia was the woman whom Caesar loved best, and in his first consulship he brought her a pearl worth 60,000 gold pieces. He gave her many presents during the Civil War, as well as knocking down certain valuable estates to her at a public auction for a song. When surprise was expressed at the low price, Cicero made a neat remark: ‘It was even cheaper than you think, because a third (tertium) had been discounted.’ Sevilia, you see, was also suspected at the time of having prostituted her daughter Tertia to Caesar.”

Suetonius’s description of Caesar the great seducer has come down through the ages: Caesar is said to have been tall, fair, and well built, with a rather broad face and keen, dark-brown eyes. His health was sound, apart from sudden comas and a tendency to nightmares which troubled him towards the end of his life; but he twice had epileptic fits while on campaign. He was something of a dandy, always keeping his head carefully trimmed and shaved; and has been accused of having certain other hairy parts of his body depilated with tweezers. His baldness was a disfigurement which his enemies harped upon, much to his exasperation; but he used to comb the thin strands of hair forward from poll, and of all the honours voted him by the Senate and People, none pleased him so much as the privilege of wearing a laurel wreath on all occasions – he constantly took advantage of it.

That Caesar employed his sexuality to gain his political ends won him no friends in the conservative camp. To the optimates, Caesar had become the incarnation of all the new abominations of the time: the young, unscrupulous libertine who used and abused marriage to suit his sexual or political urges. Although there is much scholarly wrangling over his exact motives, Caesar’s second marriage in 67 B.C. to Pompeia, a 21-year-old granddaughter of his erstwhile enemy Sulla, was no doubt a tactical move to bridge the gap between himself and the conservative party. Besides, the political conditions of the time did not favor the popular cause. That Caesar was able to affect this marriage attests to his political skill and the shortness of political memories at Rome.

His marriage to Pompeia put Caesar on the opposite side of the cuckold’s horns. Yearly in the first week of December a religious ceremony known as Bona Dea (Good Goddess) was held in the house of the chief magistrate in Rome, under the leadership of his wife assisted by the six Vestal Virgins. It was a ceremony from which men were excluded under the penalty of banishment. Since Roman law had no provision for capital punishment, banishment was the severest penalty a citizen could suffer. In 62 B.C. the Bona Dea was held in Caesar’s house and, as was the custom, Pompeia officiated at the ceremony.

During the observance, Publius Clodius, a well-known libertine and political leader of the populares, was discovered among the celebrants dressed in woman’s clothing. It was alleged that he was the lower of Caesar’s wife, and the sacrilege of a liaison at the Bona Dea was intended to heighten their lovemaking. The historical biographer

Plutarch, who invariably tries to save his subject embarrassment, explains the love affair somewhat differently: “Publius Clodius was a patrician by descent, eminent both for his riches and eloquence, but in a licentiousness of life and audacity exceeded the most noted profligates of the day. He was in love with Pompeia, Caesar’s wife, and she had no aversion to him. But there was strict watch kept on her apartment, and Caesar’s mother, Aurelia, who was a discreet woman, being continually about her, made any interview very dangerous and difficult.”

Plutarch also gave a full account of the events which lead up to the discovery of Clodius: “As Pompeia was at that time celebrating this feast, Clodius, who as yet had no beard and so thought to pass undiscovered, took upon him the dress and ornaments of a singing woman, and so came thither, having the air of a young girl. Finding the doors open, he was without any stop introduced by the maid, who was in the intrigue. She presently ran to tell Pompeia, but as she was away a long time, he grew uneasy in waiting for her, and left his post and traversed the house from one room to another, still taking care to avoid the lights, till at last Aurelia’s woman met him, and invited him to play with her, as the women did among themselves. He refused to comply, and she presently pulled him forward, and him who he was and whence he came. Clodius told her he was waiting for Pompeia’s own maid, Abra, being in fact her own name also, and he said so, betrayed himself by his voice. Upon which the woman, shrieking, ran into the company where there were lights, and cried out she had discovered a man. The women were all in a fright, Aurelia covered the sacred things and stopped the proceedings, and having ordered the doors to be shut, went about with lights to find Clodius, who was got into the maid’s room that he had come in with, and was seized there. The women knew him, and drove him out of doors, and at once, that same night, went home and told their husbands the story.”

The next morning, the news was all over Rome of the impious attempt Clodius had made against the wife of the chief magistrate and how he ought to be punished not only for adultery but also for his public sacrilege. Senators of the optimate party gave evidence against him, charging him, among other crimes, with having has sexual relations with his own sister, the beautiful but morally dissolute Clodia, who despite her great wealth and ancient patrimony had taken to streetwalking. But the people, with whom Clodius was very popular, set themselves against the nobility, and the judges were afraid to provoke the multitude and renew civil war. Caesar at once divorced Pompeia but, being summoned as witness against Clodius, claimed he had nothing to accuse him of. Since this was of course paradoxical, the prosecutor asked Caesar why had he in that case divorced his wife. Caesar’s terse reply had been often quoted as evidence of his utter amorality: “Because my wife must be above suspicion.”

J.F.C. Fuller, in his biography of Caesar, captures what well may have been the essence of Caesar’s reasoning: “When the scandal was first made public, Caesar must have been intensely annoyed, but after he had divorced his wife, whether she were guilty or not, because she became a thing of the past, to wreak vengeance on Clodius was to think and act in terms of the past. Better to look to the future and profit by the incident. If Clodius were bold enough to commit sacrilege, which he certainly had done, and probably had seduced, or attempted to seduce, the wife of the Chief Pontiff, he must be a man of astonishing audacity, and as such men are not to be picked up at every street corner, would not it be more profitable to befriend him, as the gold of Crassus (who bought out a majority of the jurors for Clodius’s acquittal) had enabled Caesar to do, than to make him a deadly enemy?”

Caesar’s governorship of Spain and his military exploits in Gaul also enhanced his reputation as a lover. Suetonius preserved another of the ribald verses sung by Caesar’s legionnaires: Home we bring our bald whoremonger; Romans, lock your wives away! All the bags of gold you lent him went his Gallic tarts to pay.

But the “Gallic tarts,” it seems, were not simply reserved for Caesar. All accounts indicate that Caesar considered sexuality a good way to heighten morale. Often after a crucial victory he relieved his troops of all military duties and allowed them to carry on as wildly as they pleased. One of his boasts reveals his feelings about the matter: “My men in fight just as well when they are thinking of perfume.”

Caesar’s sexuality did not always win him the objectives he sought. Despite his great victories in Gaul and the military defeat of Pompey, which had virtually made him Dictator, Caesar’s profligacy was becoming the object of frequent aspersions by commoner and aristocrat alike. Even members of his own party spoke out against his open, evermounting dissoluteness. In mock seriousness, one Helvius Cinna informed a number of people of his intention of drawing up a piece of legislation “legitimizing” his marriage with any woman, or women he pleased – for the procreation of children.” Suetonius, in attempting to emphasize the bad name Caesar had won for his natural and unnatural vices, recorded that a political enemy once referred to Caesar as: “Every woman’s husband and every man’s wife.”

Caesar’s last marriage, which occurred in 59 B.C., was to Calpurnia. She remained his wife until his assassination in 44 B.C. Like the previous two, this marriage had its political motives. The usual conservative outcry was heard once again. Cato the Younger complained that the state had now become a mere matrimonial agency. As for Caesar, he hardly saw his wife because military obligations had increasingly taken him from Rome.

After the defeat of Pompey, Caesar found himself in Africa, the land of his most famous affair of the heart. Cleopatra was not the first woman of royalty to be Caesar’s mistress. It had been an open secret for some time in Roma that Caesar had been giving full reign to his passions in Africa and that he had now developed a particular liking for royalty. He is said to have had an affair with Eunoe, wife of the Moor Bogudes, King of Mauretania. As a result, the rumor went, both king and queen were supposed to have profited handsomely. Despite the romantic legend it created, Caesar’s affair with Cleopatra brought him nothing but trouble. It caused him to an unnecessary war in Egypt, which almost cost him his life, and forced him into too long an absence from the Roman political scene. A case can also be made that this affair was one of the principal causes for Caesar’s assassination.

The real motives behind Caesar’s occupation of Alexandria, the then royal citadel of Egypt, continue to be a source of scholarly controversy. Once there, however, he found himself in the midst of a royal struggle for power between Cleopatra and her coregent brother, Ptolemy. According to Plutarch, Ptolemy was supposed to have demanded Caesar’s departure, preferring to settle matters with his sister by himself. Caesar who took umbrage at Ptolemy’s remarks, called for Cleopatra, who was in forced retirement. The story of Cleopatra’s first meeting with her Roman suitor is the cornerstone of the great romantic legend and this is Plutarch’s account of it: “She took a small boat, and one only of their confidants, Apollodorous, the Sicilian, along with her, and in the dusk of the evening landed near the palace. She was at a loss how to get in undiscovered, till she thought of putting herself into the coverlet of a bed and lying at length, whilst Apollodorus tied up the bedding and carried it on his back through the gates to Caesar’s apartment. Caesar was first captivated by this proof of Cleapatra’s bold wit, and was afterwards so overcome by the charm of her society that he made reconciliation between her and her brother, on the condition that she should rule as his colleague in the kingdom.”

Dio in writing his version of this incident told a different story. First, he portrayed Cleopatra as the initiator of the meeting; and second, he added a decidedly sexual cast to the entire episode: “Cleopatra, it seems, had at first urged with Caesar her claim against her brother by means of agents, but as soon as she discovered his position (which was very susceptible, to such an extent that he had his intrigues with ever so many other women – with all, doubtless, who chanced to come in his way) she sent word to him that she was being betrayed by her friends and asked that she be allowed to plead her case in person. For she was a woman of surpassing beauty, and at that time, when she was in the prime of her youth, she was most striking; she also possessed a most charming voice and a knowledge of how to make herself agreeable to every one. Being brilliant to look upon and to listen to, with the power to subjugate very one, even a love-sated man already past his prime, she thought that it would be in keeping with her role to meet Caesar, and she reposed in her beauty all her claims to the throne. She asked therefore for admission to his presence, and on obtaining permission adorned and beautified herself so as to appear before him in the most majestic and at the same time pity-inspiring guise. When she had perfected her schemes she entered the city (for she had been living outside of it), and by night without Ptolemy’s knowledge went into the palace. Caesar, upon seeing her and hearing her speak a few words, was forthwith so completely captivated that he at once before dawn, sent for Ptolemy and tried to reconcile them, thus acting as advocate for the very woman whose judge he had previously assumed to be.”

Ptolemy, who quickly realized that Caesar could no longer be expected to act as a neutral party, reportedly went to pieces upon hearing of his sister’s visit to Caesar’s bedchamber. He ran out of the palace crying that he had been betrayed, and at last tore the crown from his head and cast it away. His actions greatly disturbed the Alexandrian populace, who were already resentful of the high-handed Roman occupation of their harbor and royal palace. War erupted shortly thereafter, and Caesar, whose armed forces at the time amounted to very little, was caught off guard and in one of the skirmishes almost lost his life.

Sir William Tarn, a modern scholar, placed Caesar’s attraction to Cleopatra in a different light. The 22-year-old princess, he held, was not remarkably beautiful but possessed and extraordinary seductiveness. She was intensely alive and quite fearless, highly intelligent, and conversant in a number of languages. The “essence of her nature,” he wrote, lay not in her sexuality but in her ambition, a thing for which the always striving Caesar had the highest regard. She combined charm and brain remorselessly in the pursuit of power. It was evidently this “ambition” that caused the Romans to look up her with such suspicion. They feared her, hated her, and accused her of the vilest vices, including sorcery, beast-worship, and willful castration of men. Yet all these calumnies only built up, as Tarn held, “the monument which still witnesses to the greatness in her. For Rome, who had never condescended to fear any nation or people did in her time fear two human beings: the one was Hannibal, and the other was a woman.”

The so-called Alexandrian war, which was an affair of Caesar’s heart and not his head, lasted from early October 48 B.C. to March of the following year. And though civil war had once again erupted at Rome, Caesar decided on a 2-month honeymoon cruise to celebrate his Egyptian victory. The historian Appian claimed that the lovers were accompanied by a fleet of 400 ships, which many hold as an exaggeration since there was not sufficient time to organize such a vast fleet. Suetonius related that during this cruise Caesar often feasted Cleopatra until dawn, “and they would have sailed together in her state barge nearly to Ethiopia and his soldiers consented to follow him.”

Sometime late in 46 B.C., Caesar invited Cleopatra to Rome. She arrived with a large entourage, her newly acquired boy husband, and an infant son reputed to be Caesar’s. He installed her and her party in his suburban mansion on the Janiculan Hill beyond the Tiber. That Caesar kept another mistress was no scandal, but that she was an alien queen, as Dio related “incurred the greatest censure from all because of his passion for Cleapatra – not now the passion he had displayed in Egypt (for that was a matter of hearsay), but that which was displayed in Rome itself. For she had come to the city with her husband and settled in Caesar’s own house, so that he too derived an ill repute on account of both of them.”

Caesar’s child by her also caused much scandal. The Romans were shocked at considering a half-alien boy an heir to their state. Caesar did little to stop the murmuring. For instance, he allowed her to call the boy “Caesarion.” A number of Caesar’s close friends, including Mark Antony, testified before the Roman Senate on the boy’s legitimacy. But another friend, Gaius Oppius, seems to have felt the need of clearing Caesar’s reputation. He published a book to prove that the boy could not have been fathered by Caesar at the time.

The long-neglected Calpurnia was also a cause for much scandal. Many felt that she had been greatly wronged. Married for 13 years, she spent most of that time left alone by a travel-loving husband, and, with Cleopatra’s arrival, she compelled to receive rival into her own household. Yet Calpurnia’s instance was but one of a thousand other women who were neither dissolute nor criminal and whose names have not survived. They were married, abandoned, and divorced from one year to the next, without regard to the age or character of their intended husbands. Politics determined their marriage beds, homes, households, and society. Often these arrangements forbade them the right to motherhood or brought them stepsons older than themselves at their husband’s table. They often had to endure the shame of being openly superseded by freedwomen, slaves, noble mistresses, and sometimes queens.

The degree to which Caesar’s affair with Cleopatra led to his undoing is still in question. Doubtless there were better reasons for his assassination in 44 B.C. than his open promiscuity. The assassins themselves appear to have acted mainly to thwart what they considered Caesar’s kingly ambitions. But it was intolerable that Caesar should ostentatiously make public his private vices. In particular, the installation of a long-hated foreign queen and the display of Caesarion in Rome, if not direct causes, were at least contributory factors. No doubt these incidents helped create the general atmosphere of distrust and suspicion in which the assassins acted. In the end, undoing not so much in themselves but that in his great passions he often neglected to calculate the results.

HISTORY OF LOVE

ancient Rome,

Cleopatra,

Facebook,

Google,

Historical essay,

intellectual history,

Joh H Collins,

Julius Caesar,

marriage,

Stanley Pacion,

YouTube lecture series

Thursday, July 17, 2008

NERO: SEX AND LOVE in Ancient Rome

THE LIFE OF NERO:

SEX AND THE FALL OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE

www.youtube.com/StanleyPacion

http://www.stanleypacion.com/home.html/

http://stanley.pacion.googlepages.com/sexandhistory

http://www.indiaeveryday.in/video/u/StanleyPacion.htm?ss=true

As of this date, 14 August 2013, my YOUTUBE Channel has received 21l,000 + Single Page Visits, Video Views! A Google Search of the terms Stanley Pacion YouTube Channel yields a result count of in the millions.

Please SUBSCRIBE BUTTON

Nero’s sexual excesses led to corruption of all Roman institutions.

Stanley J. Pacion

This article presents an historical essay on sex and love in the court of the Emperor Nero. It was originally published in the medical journal, Medical Aspects of Human Sexuality, Volume V, March 1971, pp.170-185. The journal is now defunct, and its availability is severely circumscribed because it is usually found in the archive stacks of university, medical libraries where access to the general public is often denied. Still I was pleasantly surprised to find some online references to this article. I have taken this opportunity to edit and rewrite the essay, but I have also tried to retain its original content and style.

The best source of information regarding Nero is in On the Life of the Caesars, or as it is commonly known by its English title, The Twelve Caesars by Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus, known over the generations as Suetonius. This expose of the personal lives of the first twelve Roman emperors shocks readers even today. Suetonius’ explicit depictions of Nero’s sexual exploits border – some will argue transcend – the pornographic. In older translations of the work, parts of the life of Nero are either deleted, asterisks mark off the censored passages, or they are left in the original (a practice which induced many a schoolboy to improve his Latin). Generally speaking, Suetonius' history can be described as very lascivious, gossipy, filled with great story telling, and, often, downright funny.

Those readers who followed the links to online sources will soon ascertain just how relatively few are the actual, real sources to the lives of the of the Caesars, especially those at the helm during the earlier years of the Roman Empire. This may be an wholesale exaggeration, but I remember a professor of classics claim that there is more evidence for the historical Jesus than there is evidence in for the life of Julius Caesar. As has so often been remarked, the triumph of barbarism and Christian was relatively complete. The libraries of antiquity, and the writings of the ancient essayists and historians were destroyed. The monks simply scraped off the writings from the lamb skin parchments before them and replaced the ancient script with the new ecclesiastical doctrine. Then when the next scribe came along he merely scraped off the writings of the previous scribe and rewrote the same or similar passage either from or about Scripture on the now blank parchment, so on and so on. The operating principle here was not the preservation of historical scripts, or Scripture, but a maxim which held that idle hands were the devils tools.

Also, another central point of fact, the barbarian tribes which crossed the borders of the Empire were largely illiterate, and so were their commanders in chief. They burned and they pillaged. There is no way to describe how long this era of absolute destruction reigned until one remembers that most of the knowledge of classical antiquity remained lost to Western Europeans until its rebirth in Italy, well-nigh a thousand years later during the thirteenth and fourteenth century, a period which is commonly called the Renaissance.

Readers will find me addressing my credentials when I comment on this period of ancient Roman history in my account of love and sex during Julius Caesar's political rise and subsequent seizure of power. But for now my sense of Roman history and society during Nero's time for the purpose of this article rests on the text that that has come down to us from Suetonius. Historians have to the scholar remarked that the history of Nero’s reign is highly conjectural, because no historical sources have survived which were contemporaneous with Nero's period. In a word, no primary sources from Nero's court remain. Actually there is nothing surprising in this central fact. We know that so much of the literature from all of antiquity has been lost anyway.

I will continue this account of Nero's court with an a school-book exercise called, or commonly referred to as an explanation of the text. There is no doubt that Suetonius does retain both the book knowledge, then extant in the ancient world libraries, and what was preserved in the oral tradition. It is true that he was a member of the patrician class, and that this group had suffered terribly in the hands of Nero and his guards. No doubt Suetonius, like so many other Romans, had axe to grind when it came time to account for the emperor. But his is one of the only historical accounts remaining. The Twelve Caesars remains one of the most famous books to reach us from classical antiquity. So it is to Suetonius chapter on Nero that I turn to abstract the quality and meaning of life of the Roman court during the mid-part of the first century during our common era.

GOOD BOY GONE BAD

When Suetonius begins his account of Nero's life he sets the theme, Nero's is a relatively good life story, he might be even construed a good man, who has gone bad. Whatever the eventual consequences of his reign, the best intentions marked Nero’s first years as the emperor. Suetonius writes, “…he promised to model his rule on the principles laid down by Augustus, never missed an opportunity of being generous or merciful.” He lowered taxes, strengthened the economy, lessened the severity of Roman jurisprudence, and through his influence and money provided for a general cultural renaissance in Rome.

For Suetonius, the cause for the transformation of Nero’s rule from virtue to depravity, violence, and unmitigated squander was sexual. This theme about sexual excess ever mounting desires, its insatiability, and its ultimate regression into absolute depravity repeats itself time and again in Suetonius' account. I might personally argue that it is Suetonius himself who can be held responsible for Christianity's long time play on the self-same theme in the literature of its Saints. Early Christian writers, almost to the man, argue that one engaged the carnal lust multiplies in a downward progression. In the end, they hold, it brings about personal destruction, and great woe and misfortune to all those in the company of depravity. In like measure, it, too, is a theme upon which Suetonius seems never to tire harping. He repeats it endlessly in his account of Nero's life.

The young, handsome boy obsessed by music (he played the lyre), the theater, art, and given to public recitals of his poems, began to hold great dinner parties to which he invited prostitutes. What follows is a horrifying account of the rapacity and the extremes of sexuality. Nero’s life once again marches to illustrate Suetonius’ central theme: the desire for carnal pleasure multiplies and ultimately leads to perversion. Though the young Nero’s first experiments with debauchery were relatively mild, his sexual appetites soon drove him through the catalog of lusts:

“Not satisfied with seducing free-born boys and married women, Nero raped the Vestal Virgin Rubria… Having tried to turn the boy Sporus into a girl by castration, he went through a wedding ceremony with him – dowry, bridal veil and all – which the whole Court attended; then treated him as a wife. He dressed Sporus in the fine clothes normally worn by an Empress and took him in his own litter not only to every Greek assize and fair, but actually through the Street of Images at Rome, kissing him amorously now and then. A rather amusing joke is still going the rounds: the world would have been a happier place had Nero’s father Domitius married that sort of wife.”

Suetonius employs a dark, sinister humor, but the reader can not hold back a smirk.

The symbolic meaning of Nero’s rape of the vestal virgin Rubria was not lost to Suetonius’ original readers, even those of the early second century of the common era. The Six Vestal Virgins were young women of noble families who dedicated themselves to guarding the Sacred Heart in the temple of Jupiter. These women submitted themselves to regular vaginal examination. If it were determined that a maid had allowed herself to be violated, even, as in the case of Rubria, if the act had been forced upon her, raped, she was bound and hurled alive from the Tarpeian Rock to the Forum some four-hundred feet below.

The Sacred Hearth itself represented, among other things, traditional Roman morality, which was very different from the moral standard developing during Nero’s day. In sexual terms; it meant chastity for unmarried women, fidelity in wedlock, and the sanctity of the family, a series of strong imperatives that held death better than dishonor. Nero’s rape of the vestal virgin, besides the fact that it sentenced her to die, symbolized an assault against the entire moral order. It was a sacrilege, a willful trespass against all things holy, and signaled the commencement of a reign of depravity.

ROMAN SOCIAL DEPRAVITY

Suetonius’ anecdotal account of Nero’s perversions is more than a simple indictment of a single personality. Interpreted broadly, it represents an attack against the whole of Roman society, especially the upper classes. Nero, father of the country and head of state, was symptomatic of the disease that had invaded the entire social body. In his perversity Nero found many eager accomplices: “Whenever he floated down the Tiber to Ostia, or cruised past Baiae, he had a row of temporary brothels erected along the shore, where a number of noblewomen, pretending to be madams, stood waiting to solicit his customs.”

Suetonius’ implication is unmistakable. Society had become a bordello. The state no longer responded to the demands of empire, but to the beckons of madams. Lust was turning all social values topsy-turvey. Passion, Suetonius argues, not reason and might, governed the Roman imperium. Indulgence in sexuality had subordinated the vast resources of the dominion to orgy. “His feasts now lasted from noon till midnight, with occasional break for diving into a warm bath or, if it were summer, into snow-cooled water. Sometimes he would drain the artificial lake in the Campus Martius, or the other in the Circus, and hold public dinner parties there, including prostitutes and dancing girls from all over the city among his guests.”

Nero’s flagrant disregard for traditional Roman morality reached its peak in his attacks on the family. He had an unnatural attachment to his mother. The seriousness with which antiquity viewed the crime of incest is brilliantly presented in the play Oedipus Rex. Even in Nero’s day the crossing of this sexual line had terrible repercussions. Once again, Suetonius works his favorite theme: the sexual instinct, because it constantly seeks new forms of arousal, proceeds to the corruption of all moral norms. Addiction to sex, Suetonius seems to say, has a terrible end. “The passion he felt for his mother, Agrippina, was notorious; but her enemies would not let him consummate it, fearing that, if he did, she would become even more powerful and ruthless than hitherto. So he found a new mistress who was said to be her split and image; some say that he did, in fact, commit incest with Agrippina every time they rode in the same litter – the state of his clothes when he emerged proved it.”

For Suetonius, the sexual need not only doubles upon itself and falls to perversion, it also makes for violence. The destruction, mayhem, and brutality that marked Nero’s reign had its direct cause in sexuality. From its earliest years the Roman state was militaristic; war was a commonplace. Mildness and meekness were never considered virtues. But Roman martial brutality usually had one specific end: subjugation of territories in order to increase revenues for the state treasury. Nero, however, practiced brutality for a different reason. In his eager pursuit of new erotic forms, sadism became his partner. His personal atrocities against others were extensions of his lust. Sex addiction, Suetonius seems to say, has a very sorry, sad end.MATRICIDE

Nero’s murder of his mother, Agrippina, is often represented as the most startling example of this kind of sadism. Nero attempted the murder at least four times. Agrippina herself, largely because of Suetonius account of her life and murder, has become the second most famous mother in Western history. Though Nero’s motives for the crime were mixed, Suetonius shows that there was a strong sexual undertow. This long excerpt is a case study of oedipal lust-rage and one of the most famous passages in Roman literature:“…he had a collapsible cabin boat designed which would either sink or fall in on top of her. Under pretense of a reconciliation, he sent the most friendly note inviting her to celebrate the Feast of Minerva with him at Baiae, and on her arrival made one of his captains stage an accidental collision with the galley in which she had sailed. Then he protracted the feast until a late hour, and when at last she said: 'Nero, I really must get back to Baiae,' offered her his collapsible boat instead of the damaged galley. Nero was in a very happy mood as he led Agrippina down to the quay, and even kissed her breast before she stepped aboard. He sat up all night, on tenterhooks of anxiety, waiting for news of her death. At dawn Lucius Agermus, her freedman, entered joyfully to report that although the ship had foundered, his mother had swum to safety, and he need have no fears on her account. [Here we have a great example of Suetonius uses of a very dark, but pointed sense of humor.]For want of a better plan, Nero ordered one of his men to drop a dagger surreptitiously beside Agermus, whom he arrested at once on a charge of attempted murder.

“After this he arranged for Agrippina to be killed, and made it seem as if she had sent Agermus to assassinate him but committed suicide on hearing that the plot had miscarried.”

The kissing of Agrippina’s breasts before he led her down the pier to what he believed would be her death is only one example of Nero’s sadistic bent. Suetonius supplies other more gruesome details, ones which bear a necrophilia stamp: It appears that Nero rushed off to examine Agrippina’s corpse, handling her legs and arms critically and, between drinks, discussing their good and bad points.”

Sadism animated all of Nero’s love relations with women. He murdered his favorite aunt by ordering her doctors to give her a laxative of fatal strength. He treated his first wife so badly – he even tried to strangle her on a number of occasions – that a few of his friends mustered enough courage to criticize him. Though he doted on his second wife, he kicked her to death while she was pregnant because she dared complain that he came home late from the races. Again, Suetonius account reads loud and clear, once the way to sexuality becomes unbridled, the end result invariably becomes one of awful violence.THE WAGES OF UNBRIDLED LUST

Nero not only brutally abused the marriage and familial institution, using it as means to meet the demands of his ever-mounting lusts, he also openly and deliberately mocked it. Nero’s love for his freedman Doryphorus, the boy Sporus, and a host of other male friends always involved a mock marriage. The holiest of Roman institutions was his plaything, an instrument which he employed to heighten erotic simulation. Suetonius works a dark theme. Sex had undermined all social values. Motherhood, marriage, the family, every principle guaranteed by the Sacred Hearth, fell to a sadistic lust. The unchecked sexual instinct had reduced Roman society to a horrible travesty of its former self.

Nero’s debauchery had an effect throughout the empire. Lust, not right, became the standard in judicial procedure. Felons of all sorts would gain executive clemency from Nero if they confessed to sexual excess. “He was convinced that nobody could remain sexually chaste, but that most people concealed their secret vices; hence, if anyone confessed to obscene practices, Nero forgave him all his other crimes.” All a criminal had to do, according to Suetonius, is confess to the Emperor a crazy, perverted sexuality and his or her crimes, whatever their seriousness, would be pardoned. In Nero's court, wanton vice and penchant for debauchery became the touchstones for assaying morality. All had been turned upside down. Like all other things he touched, Nero perverted the once proud legal code of the Roman state.

Sex, also, dictated the empire’s economic policies. Though during the early years of his reign Nero actually fattened the treasury, his later years showed incredible profligacy. Excess in sexuality, Suetonius suggests, made for excess in spending, especially in the building of pleasure palaces. The vast fortunes that Nero expanded in creating places of sensual delight were fantastic, forcing him in the end to bankruptcy. Suetonius gives a good account of some of these projects:

“He built a palace, stretching from the Palatine to the Esquiline, which he called “The Passageway”; and when it burned down soon afterwards, rebuilt it under the new name of “The Golden House.” The following details will give some notion of its size and magnificence. A huge statue of himself, 120 feet high, stood in the entrance hall; and the pillared arcade ran for a whole mile. An enormous pool, more like a sea than a pool, was surrounded by buildings made to resemble cities, and by a landscape garden consisting of ploughed fields, vineyards, pastures, and woodlands – where every variety of domestic and wild animal roamed about. Parts of the house were overlaid with gold and studded with precious stones. All the dining-rooms had ceilings of fretted ivory, the panels of which could slide back and let a rain of flowers, or of perfume from hidden sprinklers, shower upon his guests. The main dining-room was circular, and its roof revolved slowly, day and night, in time with the sky. Sea water, or sulphur water, was always on tap in the baths. When the palace had been decorated throughout in this lavish style, Nero dedicated it, and condescended to remark: “Good, now I can at least begin to live like a human being!”

The bankruptcy of the economy signaled the mortal bankruptcy of the state. To obtain the additional funds he needed to complete his architectural projects, he resorted to extortion, robbery, and blackmail. In committing these crimes his private bestiality grew into a public affair. One, among his many atrocities, was a wholesale massacre of the nobility. And then, finally, the burning of Rome, crimes from which he profited. Addiction, in this case sex addiction, leads to crime, and the greater the addiction, the greater the crimes need to satiate its ever mounting demands.

But despite his violent depravity, Nero had grown increasingly ineffectual. When challenged by the revolt of his general, Galba, and rising power of the barbarian chieftain, Vindex, his only response was obscenity. “Yet he made not the slightest attempt to alert his lazy and extravagant life. On the contrary, he celebrated whatever good news came in from the provinces with the most lavish banquets imaginable, and composed comic songs about the leaders of the revolt, which he set to bawdy tunes and sang with appropriate gestures.”

Suetonius’ sex history lesson is clear. Excessive and perverted sexuality made for moral decadence. Rebellion, treason, arson, murder, or extortion could be practiced without fear of retribution. The Roman martial tradition of might and action was turned into a kind of comic relief, some bawdy theatric. Forced at last to act against the Gauls under Vindex, Nero’s first military preparation was “finding enough wagons to carry his stage equipment and arranging for the concubines who would accompany him to have male haircuts and be issued with Amazonian shields and axes.”

Through the life of Nero, Suetonius tackles the cosmic question: “Why did Rome fall?” and creates an answer which has lasted the centuries. For Suetonius, Rome saw its decline in the age of the first Caesars, particularly during the reign of Nero. In this sense, Suetonius is a moralist, not a pornographer. He employs an obvious sensationalism to gain his reader’s ear, to cement interest. His gossipy revelations of the intimate behavior of the high and powerful are not ends in themselves. They are devices used to underscore a theme of decadence, and to pinpoint what he considered to be the chief cause for the downward swing in Roman morality – sex. For Suetonius, all social, ethical, cultural, political and economic norms depend on the suppression of the sexual instinct. In his view, once there is adventure in carnality, no society, state, or empire can long endure.

The validity of Suetonius’ lesson is difficult to determine. If there is a link between sexual depravity and the downfall of the Roman Empire, that result was long in coming. Rome's society's indulgence in sexual depravity, after all, has had a very long history, indeed.

-->

HISTORY OF LOVE

ancient Rome,

court life of the Emperor,

decadence,

Historical essay,

intellectual history,

love,

Nero,

sex,

Suetonius,

THE TWELVE CAESARS,

vice and depravity,

violence,

YouTube

Friday, June 27, 2008

ANCIENT SPARTA'S STATE FOSTERED HOMOSEXUALITY

http://www.youtube.com/StanleyPacion

http://stanley.pacion.googlepages.com/homepage

SPARTA: AN EXPERIMENT IN STATE-FOSTERED HOMOSEXUALITY

Spartan militarism and the well-being of the state depended on sexual love between men.

Stanley J Pacion

SPARTA.This article represents an historical essay which was originally published in the medical journal, Medical Aspects of Human Sexuality, Volume IV, August 1970, pp.28-32. The journal is now defunct, and its availability is severely circumscribed since it is usually found in the archive stacks of university, medical libraries where access to the general public is often denied. Still I was pleasantly surprised to find the many online references

to this article.

I have taken this opportunity to edit and rewrite the essay, but I have also tried to retain its original content and style. Its analytical style operates under the school practice commonly referred to or called, explanation du text. The only bibliographical source I use here comes from a book commonly entitled, PLUTARCH'S LIVES. I see, Project Gutenberg uses the Arthur Hugh Clough edition, which has the original John Dryden translation from the Greek and the Project calls its online version, Plutarch: Lives of the noble Grecians and Romans.

I remember one of my professors of classics commenting that what we really knew about these figures from the ancient world could be written on the back of a postage stamp. I will have more to say about my academic training and my professors of classics later in this series on sex in antiquity. The triumph of Christianity and barbarian invasions of Europe meant the destruction of the greater part of the ancient world's literature. Very little of these ancient primary sources remain. For Sparta this central fact proves doubly true since even the archaeological evidence is scant. The ancient Spartans were interested in military might, not monuments and architecture. But there is no doubt that Plutarch does retain both the book knowledge, then extant in the ancient world libraries, and what was preserved in the oral tradition. So it is to his Lycurgus that I turn to abstract the quality and meaning of life under the Spartan constitution.

Writers have consistently depicted Spartan society as one of military heroism, of rugged, masculine self-reliance and hard-nosed practicality. Even at this date the adjective “Spartan” remains synonymous with words like brave and austere.

Yet there is another part of the traditional image of ancient Sparta, one not so commonly acknowledged. It is the rigidly controlled Sparta, a state based on a constitution which aimed to repress individuality for the sake of communal ends. State control extended even to the sexual lives of the citizen-soldiers and the women. The entire state was geared toward military efficacy and both homosexual and heterosexual expression were governed by the aim of increasing military effectiveness.

One of the first and greatest shapers of our image of Sparta is the Greek moralist and historian, Plutarch, who lived during the period of the first Roman Caesars, 46AD - 120AD. Plutarch’s sketch of the Spartan sta te appears in his life of Lycurgus, the legendary lawgiver and founder of Sparta, who lived somewhere between 700-630BC. Thus some seven hundred years separate the historian biographer and the establishment of the Spartan constitution. While there is little doubt that Lycurgus [image right] was a real historical figure, the claim that he was founder of Sparta and the author of its constitution has its source in legend. Plutarch’s Lycurgus and the Sparta he fashioned represents the traditional folk story, handed down for the generations, of a great man in a dark, remote age. Plutarch’s Sparta is, therefore, not history, though there may be some historical evidence for his account. But neither is it simply fiction or legend. Plutarch himself readily admits that nothing can be said about Lycurgus to which there would be anything like common consent. Lycurgus remains a figure steeped in historical controversy.

te appears in his life of Lycurgus, the legendary lawgiver and founder of Sparta, who lived somewhere between 700-630BC. Thus some seven hundred years separate the historian biographer and the establishment of the Spartan constitution. While there is little doubt that Lycurgus [image right] was a real historical figure, the claim that he was founder of Sparta and the author of its constitution has its source in legend. Plutarch’s Lycurgus and the Sparta he fashioned represents the traditional folk story, handed down for the generations, of a great man in a dark, remote age. Plutarch’s Sparta is, therefore, not history, though there may be some historical evidence for his account. But neither is it simply fiction or legend. Plutarch himself readily admits that nothing can be said about Lycurgus to which there would be anything like common consent. Lycurgus remains a figure steeped in historical controversy.

Homosexuality

In spite of the emphasis Lycurgus placed on regulating sexual relations, the popular image of Sparta admits hardly a trace of it. The major Utopian philosophers who eagerly adopted Lycurgus's other, especially his communal and military reforms into their respective systems make no note of his sexual arrangements. The intellectual tradition in the West has strangely abbreviated Plutarch’s pagan image of Sparta. While idealizing its martial ideals, it has censored its way of love. Even today the Wikipedia article on Lycurgus makes no mention that the primary force of his legislation involved insuring strong sex/love based bonds between men. Constitutional law of ancient Sparta mandated homosexuality. The soldier-citizens were lovers. Sex and love were used to foster allegiance, man to man, so to foster, augment the fighting spirit. The time has come -- it is actually long overdue -- to call a halt to this bowdlerization.

If for the sake of propriety Spartan marriage practices have been read out of the popular image of the society in the West, it is little wonder that its institutionalized homosexuality has received the same treatment. Yet in Plutarch’s Sparta homosexuality formed the cornerstone of the commonwealth. Older men choose young male lovers. There was no real age of consent in ancient Sparta. Childhood innocence had no meaning in the warrior state. All aspects of the life cycle were subjoined to the aim of making soldiers fit for war and the preservation of the common weal. Its practice was such an integral part of Spartan life that Plutarch writes: “By the time they were come to this age (twelve years old) there was not any of the more hopeful boys who had not a lover to bear him company.” Without a realization of the profound male love relations that animated it, no understanding of Spartan society is possible. Sparta was a homosexual state by law. As such Plutarch's account of its constitution represents a vital chapter in queer history.

the same treatment. Yet in Plutarch’s Sparta homosexuality formed the cornerstone of the commonwealth. Older men choose young male lovers. There was no real age of consent in ancient Sparta. Childhood innocence had no meaning in the warrior state. All aspects of the life cycle were subjoined to the aim of making soldiers fit for war and the preservation of the common weal. Its practice was such an integral part of Spartan life that Plutarch writes: “By the time they were come to this age (twelve years old) there was not any of the more hopeful boys who had not a lover to bear him company.” Without a realization of the profound male love relations that animated it, no understanding of Spartan society is possible. Sparta was a homosexual state by law. As such Plutarch's account of its constitution represents a vital chapter in queer history.

Like other institutions in Plutarch’s Sparta, homosexuality had as its end the preservation of the state. Lycurgus believed that love ties between men who were comrades-in-arms increased allegiance to their ranks. In a word, homosexual love promoted battlefield determination -- lovers joined in the battle field side-by-side, the lawgiver felt, made for better soldiering -- and all the better fostered the love of state.

Spartan marriage law reflected this belief. As we shall see, infrequent heterosexual relations permitted by the state and the sharing of wives were intended to break down familial attachments. The Spartan male developed no sense of responsibility toward either wife or child. Duty was directed to the commonwealth, to all its wives and children alike. By permitting male companionship to be the only source of permanent sexual gratification, Lycurgus guaranteed that love would remain in the service of the state.

Homosexuality also had the function of promoting good conduct among Spartan men. Because he viewed self-esteem as insufficient spur to honor, Lycurgus ordered lovers accountable for each other’s actions. Plutarch gives a good instance of this edict’s application: “Their lovers and favourers, too, had a share in the young boy’s honour or disgrace; and there goes the story that one of them was fined by the magistrate because the lad who he loved cried out effeminately as he was fighting.” In Sparta no behavior had consequence only to self, but always directly involved an individual dear to oneself as well. Homosexuality, by making glory as well as disrepute doubly felt, guaranteed the state optimum performance from its soldiers.

To provide ample opportunity for acquaintance and the forming of passionate attachments, Lycurgus legislated mandatory communal meals for the Spartan male. These common eating halls had two named in Greek and Plutarch comments on both of them: “…the Cretans called them andria, because only men came to them. The Lacedaemonians (The Spartans) called them phiditia, that is, by changing l into d, the same as philitia, love feasts, because that, by eating and drinking together, they had the opportunity of making friends.”

phiditia, that is, by changing l into d, the same as philitia, love feasts, because that, by eating and drinking together, they had the opportunity of making friends.”

Beside the communal meal, barrack or company life provided other opportunity for securing intimate male friendship. Its effect on marriage indicated its force in shaping Spartan life. A feeling of dread characterized the martial arrangement. The young husband, Plutarch reports, visited his bride “in fear and shame, and with circumspection.” The possibility of incurring the anger of jealous, tough barrack-lovers was more than sufficient reason for the caution and apprehension of the Spartan bridegroom. Institutionalized homosexuality created a life under continuous surveillance. A watchful and ever-present lover policed every action. There was not a time or place in Plutarch’s Sparta without someone present to put a man in mind of his duty, and punish him if he neglected it.

The life of the Spartan male, therefore, was one of constant dilemma. Though encouraged into homosexuality from youth and conditioned to it by the institutions in which he lived, the law nonetheless required him to marry. Lycurgus not only excluded bachelors from participation in the greatly appreciated naked processions of women, but also prescribed, “…in wintertime, the officers compelled them [the bachelors] to march naked themselves round the market-place, singing as they went a certain song to their own disgrace, that they justly suffered this punishment for disobeying the laws. Moreover, they were denied that respect and observance which the men paid their elders.” The need for children as well as the preservation of duty to the state inspired this contradictory legislation for Sparta. A frustrating, anxious, unfulfilled life was its product. Lycurgus may well have created the psychological source of the violence on which Spartan militarism rested.

Marriage and Women

It has often been observed that one of the key institutions for social control is marriage. Plutarch’s Sparta proves no exception to this general rule. Lycurgus legislated marriage with a special gusto, dictating the time, the length, even the qualifications of the marriage partners.

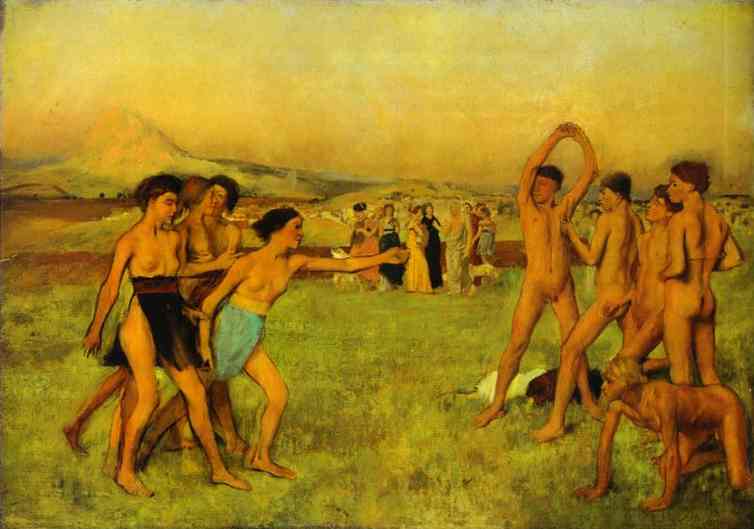

In Plutarch’s Sparta the citizen was educated for marriage. The right to love was an acquired property. Men and women earned intimacy by observing the precepts of the law. Though marital educational provisions applied equally to both sexes, the success of the marriage institution seemed largely dependent on the rearing of women. To secure their fitness for marriage, Lycurgus ordered maidens to exercise by calisthenics, wrestling, running, spear-throwing, and casting the dart. “And to the end he might take away their overgreat tenderness and fear of exposure to the air, and all acquired womanishness, he ordered that the young women should go naked in the processions, as well as the young men, and dance too in that condition at certain solemn feasts, singing certain songs, whilst the young men stood, around, seeing and hearing them.”

The ostensible aim in this kind of training was eugenic, “… that the fruit they conceived might, in strong and healthy bodies, take firmer root and find better growth, and withal that they, with this greater vigor, might be the more able to undergo the pains of childbearing.” For Lycurgus a simple principle governed human heredity: the issue of physically healthy children. Proper marital education for women insured the Spartan state a future supply of well-endowed soldiers.

The training of wo men also had another purpose in Plutarch’s Sparta. The naked public processions and naked exercises of women were incitements to marriage. The well-being of the state rested on not only the quality of its children, but also the quantity. Lycurgus, therefore, viewed celibacy as tantamount to crime. If the nudity of maidens were not sufficient inducement to move a man from bachelorhood, it became the means by which to punish him: “… those who continued bachelors,” Plutarch writes, “were in a degree disfranchised by law; for they were excluded from the sight of those public processions in which the young man and maidens danced naked…”

men also had another purpose in Plutarch’s Sparta. The naked public processions and naked exercises of women were incitements to marriage. The well-being of the state rested on not only the quality of its children, but also the quantity. Lycurgus, therefore, viewed celibacy as tantamount to crime. If the nudity of maidens were not sufficient inducement to move a man from bachelorhood, it became the means by which to punish him: “… those who continued bachelors,” Plutarch writes, “were in a degree disfranchised by law; for they were excluded from the sight of those public processions in which the young man and maidens danced naked…”

Lycurgus made no provision, however, for female celibacy. The meaning of the omission is difficult to determine from Plutarch’s account. It may reflect either a belief in the natural heterosexual lasciviousness of women, or a lack of female choice in the matter.

The wedding night also fell under the jurisdiction of Lycurgus’ legislation. In a tender passage Plutarch describes the legally prescribed ritual of consummation in Spartan society: “… she who superintended the wedding comes and clips the hair of the bride close around her head, dresses her up in mans’ clothes, and leaves her upon a mattress in the dark; afterw ards comes the bridegroom, in his every-day clothes, sober and composed as having supped at the common table, and, entering privately into the room where the bride lies, unites her virgin zone, and takes her to himself; and after staying some time together, he returns composedly to his own apartment, to sleep as usual with the other young men.”

ards comes the bridegroom, in his every-day clothes, sober and composed as having supped at the common table, and, entering privately into the room where the bride lies, unites her virgin zone, and takes her to himself; and after staying some time together, he returns composedly to his own apartment, to sleep as usual with the other young men.”

Plutarch’s portrayal of the wedding-night ritual set the whole tone for the Spartan marriage. Because the law required military exercises during the day and confinement to barracks at night, relations were difficult and rare. “And so he continues to do so, spending his days, and, indeed, his nights with them [the men], visiting his bride in fear and shame and with circumspection, when he thought he should not be observed; she, also, on her part, using her wit to help and find favorable opportunities for their meeting when company was out of the way.” The imposition was so severe, Plutarch adds, that a husband would sometimes have a child by his wife before he ever saw her face by daylight.

Lycurgus’ reason for imposing this hardship on marriage was, again, the well-being of the commonwealth. Lycurgus viewed marriage as a delicate institution, easily ruined by too active an application. Human emotions, though hotly triggered, were apt to burn themselves out in any permanent relationship. Hence the good marriage, indeed the utopian one, brought together couples, “… with their bodies healthy and vigorous, and their affections fresh and lively, unsated and undulled by easy access and long continuance with each other; while their partings were always early enough to leave behind in each of them some remaining fire of longing and mutual delight.”

By allowing marriage to import the fullest measure of delight, Lycurgus preserved the institution’s viability. He thereby insured a constant source of soldiers for the commonwealth. But Lycurgus’ restriction of sexual relations also shows hint of eugenic purpose. Both healthy and vigorous bodies as well at potent emotions, Plutarch writes, attended the moment of conception. Children who embodied the spark of their original conception was the prime aim of Lycurgus’ marriage law for Sparta.

Lycurgus’ use of marriage for the procurement of good children extended even into his notion of fidelity. While his economic reforms had dictated a community of goods, his social reforms provided for a community of wives. The basis for this sharing of married women was not orgiastic, rather it reflected the belief that children were not so much the property of their parents as of the whole commonwealth.

To insure fine breeding, Lycurgus would not allow his citizens, the future arsenal of the state, begot by first comers, but by the best men that could be found. The preservation of the commonweal, the best citizen soldiers gave wife swapping a new meaning. No narrow emotions were allowed under the Sparta constitution. All matters, including sexual favors and the begetting of children, were mandated to insure warrior of the best calibre. It has been often remark that in ancient Sparta soldiering went under the banner "one for all, and all for one" that motto extended to intimacy. The whole idea of private relations, private property, was an anathema to the Spartan value system, and excluded under constitutional law.

“Lycurgus allowed a man who was advanced in years and had a young wife to recommend some virtuous and approved young man; that she might have a child by him, who might inherit the good qualities of the father, and be a son to himself. On the other side, an honest man who had love for a married woman upon account of her modesty and well-favouredness of her children, might, without formality, beg her company of her husband, that he might raise, as it were, from his plot of good ground, worthy and well-allied children for himself.” Neither adultery nor adulterers existed in Plutarch’s Sparta, for the concept had no meaning. In a state whose very existence depends upon a high birth rate, fidelity was a sentiment of little consequence.

The Masculine Ideal

In Plutarch’s account of the Spartan commonwealth the love of men was transformed into the love of the masculine. The brunt of Lycur gus’ legislation fell on anything which might be considered feminine. The exercise he ordered for women, though eugenic and disguised by the abstraction of equality, hid femininity beneath a muscular, masculine frame. The naked open-air processions dried the skin, removing all traces of womanly softness. For Lycurgus, only the masculine was worthy of affection. It will be remembered that the bride in Plutarch’s portrayal of the wedding night ritual had closeclipped hair and was dressed in man’s clothes. The well-being of the state, the health of the entire commonwealth depended on its correspondence to the masculine. Hardness, the hard body, was the supreme value in a state where warrior conditioning was the first and only ideal. This was the aim and meaning of Lycurgus’ legislation for Sparta.

gus’ legislation fell on anything which might be considered feminine. The exercise he ordered for women, though eugenic and disguised by the abstraction of equality, hid femininity beneath a muscular, masculine frame. The naked open-air processions dried the skin, removing all traces of womanly softness. For Lycurgus, only the masculine was worthy of affection. It will be remembered that the bride in Plutarch’s portrayal of the wedding night ritual had closeclipped hair and was dressed in man’s clothes. The well-being of the state, the health of the entire commonwealth depended on its correspondence to the masculine. Hardness, the hard body, was the supreme value in a state where warrior conditioning was the first and only ideal. This was the aim and meaning of Lycurgus’ legislation for Sparta.

http://stanley.pacion.googlepages.com/homepage

SPARTA: AN EXPERIMENT IN STATE-FOSTERED HOMOSEXUALITY

Spartan militarism and the well-being of the state depended on sexual love between men.

Stanley J Pacion

SPARTA.This article represents an historical essay which was originally published in the medical journal, Medical Aspects of Human Sexuality, Volume IV, August 1970, pp.28-32. The journal is now defunct, and its availability is severely circumscribed since it is usually found in the archive stacks of university, medical libraries where access to the general public is often denied. Still I was pleasantly surprised to find the many online references

to this article.

I have taken this opportunity to edit and rewrite the essay, but I have also tried to retain its original content and style. Its analytical style operates under the school practice commonly referred to or called, explanation du text. The only bibliographical source I use here comes from a book commonly entitled, PLUTARCH'S LIVES. I see, Project Gutenberg uses the Arthur Hugh Clough edition, which has the original John Dryden translation from the Greek and the Project calls its online version, Plutarch: Lives of the noble Grecians and Romans.

I remember one of my professors of classics commenting that what we really knew about these figures from the ancient world could be written on the back of a postage stamp. I will have more to say about my academic training and my professors of classics later in this series on sex in antiquity. The triumph of Christianity and barbarian invasions of Europe meant the destruction of the greater part of the ancient world's literature. Very little of these ancient primary sources remain. For Sparta this central fact proves doubly true since even the archaeological evidence is scant. The ancient Spartans were interested in military might, not monuments and architecture. But there is no doubt that Plutarch does retain both the book knowledge, then extant in the ancient world libraries, and what was preserved in the oral tradition. So it is to his Lycurgus that I turn to abstract the quality and meaning of life under the Spartan constitution.

Writers have consistently depicted Spartan society as one of military heroism, of rugged, masculine self-reliance and hard-nosed practicality. Even at this date the adjective “Spartan” remains synonymous with words like brave and austere.